Display changes

Labels: John Dewhirst, Tuol Sleng

Cambodia - Temples, Books, Films and ruminations...

Labels: John Dewhirst, Tuol Sleng

Labels: DC Cam, Tuol Sleng

Another bedstead with symbols of imprisonment, initiated when the detention center was opened as a museum in 1980

Another bedstead with symbols of imprisonment, initiated when the detention center was opened as a museum in 1980Labels: Tuol Sleng

I'm reading through the final manuscript of To Cambodia With Love and my palms are sweating. Kim, the series editor, has just sent it to me and told me I have a day to read it through as the final deadline has arrived like a runaway train and my desire for perfection is just about to pass its sell-by date. I've procrastinated long enough, now it's time to face the music and produce what I promised to ThingsAsian, the publishers, what seems like a lifetime ago. Kim has done a fabulous job in picking up the pieces I sent her and I'm very proud of everyone's combined efforts. Nothing is certain in publishing though it looks like TCWL might be out in a few months - but keep it under your hat for the moment.

I'm reading through the final manuscript of To Cambodia With Love and my palms are sweating. Kim, the series editor, has just sent it to me and told me I have a day to read it through as the final deadline has arrived like a runaway train and my desire for perfection is just about to pass its sell-by date. I've procrastinated long enough, now it's time to face the music and produce what I promised to ThingsAsian, the publishers, what seems like a lifetime ago. Kim has done a fabulous job in picking up the pieces I sent her and I'm very proud of everyone's combined efforts. Nothing is certain in publishing though it looks like TCWL might be out in a few months - but keep it under your hat for the moment.Labels: Chum Mey, To Cambodia With Love, Tuol Sleng

Labels: Phnom Penh, Pont de Verneville, Tuol Sleng

Labels: Khmer Rouge Tribunal, S-21, Tuol Sleng

Labels: John Pilger, S-21, Tuol Sleng

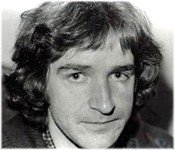

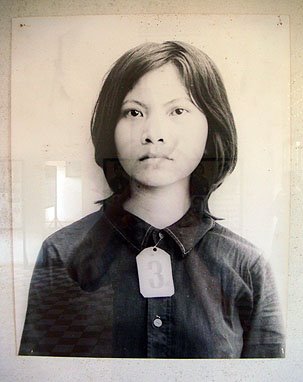

The case of 26-year-old British teacher John Dewhirst was in the news again today with a report in The Times newspaper and another by the BBC. Dewhirst (pictured) was in the wrong place at the wrong time when he was captured by a Khmer Rouge naval patrol, tortured at Tuol Sleng and executed just weeks before the Khmer Rouge regime was toppled by the invading Vietnamese army in 1979. He was the only known Briton to have been jailed in S-21 and with the trial of the prison's chief Duch underway in Phnom Penh, the stories appeared today. Also read other articles on John Dewhirst here. Dewhirst's fellow crew member Kerry Hamill also perished and filmmaker Annie Goldson is to make a documentary, Brother Number One, for New Zealand television charting the search for the truth about what happened to Hamill by his younger brother, champion rower and Olympian Rob Hamill.

The case of 26-year-old British teacher John Dewhirst was in the news again today with a report in The Times newspaper and another by the BBC. Dewhirst (pictured) was in the wrong place at the wrong time when he was captured by a Khmer Rouge naval patrol, tortured at Tuol Sleng and executed just weeks before the Khmer Rouge regime was toppled by the invading Vietnamese army in 1979. He was the only known Briton to have been jailed in S-21 and with the trial of the prison's chief Duch underway in Phnom Penh, the stories appeared today. Also read other articles on John Dewhirst here. Dewhirst's fellow crew member Kerry Hamill also perished and filmmaker Annie Goldson is to make a documentary, Brother Number One, for New Zealand television charting the search for the truth about what happened to Hamill by his younger brother, champion rower and Olympian Rob Hamill.Duch stands accused of torture, crimes against humanity and premeditated murder on a massive scale. It is alleged that he oversaw the deaths of more than 10,000 people. The Khmer Rouge killed up to two million people in less than four years. Ms Holland's brother, John Dewhirst, was among the victims. In 1978, the 26-year-old teacher was captured, tortured and killed at the notorious Tuol Sleng prison. He was the only Briton among 17,000 Cambodians to die there. Taking a holiday from his job as a teacher, he had been sailing through the Gulf of Thailand with two friends, when their boat strayed into Cambodian waters. When it was intercepted by a Khmer Rouge patrol boat, one of the party, Canadian Stuart Glass was killed immediately.

John and the other crew member, New Zealander Kerry Hamil were taken to the now infamous Tuol Sleng prison, also known as S-21. There they were tortured until they confessed to being CIA agents, before being executed. John's sister Ms Holland, now a solicitor based in Cumbria, learned of his fate by listening to the news. Eventually the Foreign and Commonwealth office confirmed he had been captured by the Khmer Rouge, and that he was probably dead. More than 30 years on, she is still traumatised by what happened. Fighting back the tears she says: "I'm a strong person. I've had knocks over the years - I experienced the death of my husband at a young age. I imagine the effect it's had on me is similar to all those people in Cambodia - it's permanent. Where there's an ordinary death - you miss the person who was in your life, and it hurts but the pain reduces over the years. Time's a great healer. But this doesn't get any less." She recognises the impact that the brutal reign of the Khmer Rouge must have had on the Cambodian national psyche: "There must be a whole country of traumatised people - because of how they were killed and tortured."

The horrors of what happened inside S-21 are almost unimaginable. Prisoners were tortured until they wrote detailed confessions - explaining how they'd been disloyal to the regime. Then they were taken to the "killing fields" at Choeung Ek, a few kilometres outside Phnom Penh. There they were executed, often bludgeoned to death with iron bars on the orders of Duch. Victims were frequently made to dig their own graves. Duch, who was meticulous in recording those who passed through S-21 described John as a polite young man - but that didn't save him.

His confession - signed and dated the 5th of July 1978 - is entitled "Details of my course at the Annexe CIA college in Loughborough England." Among the bizarre claims is that Loughborough was one of six CIA colleges in the UK. Hilary Holland says she had no idea how John was killed until recently. She decided not to attend the trial in person. "It would be too hard, and it wouldn't achieve anything," she says. But she recognises its importance: "If this trial can in any way help any of those people - then it should happen. It's of such historical importance and it's a matter of public record. The more information that can be made available, then the better historically speaking and it might stop these things happening again."

Another story ran a couple of days ago in the New Zealand press about the fate of Kerry Hamill.Labels: John Dewhirst, Kerry Hamill, Khmer Rouge Tribunal, S-21, Tuol Sleng

For the last few years, the U.N. has been sponsoring a weary, bickering, increasingly fruitless war crimes tribunal to condemn the last five senior members of the Pol Pot regime. In the summer of 2008, I watched in disbelief as Ieng Sary, the former foreign minister, was judged "unfit" to stand trial for mental health reasons. This year, it has been the turn of the sinister Duch, the commandant of Tuol Sleng. The others on trial are Khieu Samphan, the former nominal head of state; Noun Chea, Pol Pot's deputy, and Ieng Thirith. But this month in Phnom Pehn I noticed that the papers were also filled with rumors that the UN was threatening to pull out of a trial seen as being manipulated by the nervous Prime Minister Hun Sen. The slippery Hun Sen is an ex-Khmer Rouge himself, after all, and he has many skeletons in his capacious cupboards.

On the streets, meanwhile, the most ubiquitous genocide book by far is a slender volume with the modest title, A Cambodian Prison Portrait: A Year in the Khmer Rouge's S-21. Unwrap the plastic and you enter the most harrowing memoir of them all, a first-person account of the Khmer Rouge years by a naive country painter named Vann Nath: one of only seven men to survive Tuol Sleng. Sixteen thousand others were not so lucky. Some have called Vann Nath the Goya of the genocide, which was contrived by the Maoist regime of Democratic Kampuchea between 1975 and 1979. It was a period in which the strange, secretive dictator Pol Pot - whose real name was Saloth Sar - tried to create what the British historian Philip Short has called "the first modern slave state." Upon emerging victorious from a long guerrilla war against the U.S.-backed government of Lon Nol, Pol Pot's militant Khmer Rouge emptied the cities and drove millions of people into the countryside to work in collective farms. Twenty thousand died on the road in the first few days of the regime and during the next three years and 10 months, 200,000 were executed as "traitors." In total, between 1.5 million and 2 million died. When the Vietnamese army finally drove Pol Pot back into the jungles of western Cambodia, the country was strewn with the remains of the so-called killing fields.

But the Khmer Rouge did not cease to terrorize Cambodia. Supported by China, Thailand and the U.S., Pol Pot himself fought on in the wild Cardamom Mountains near the town of Pailin, on the border with Thailand. Atrocities continued. In 1994, Khmer Rouge units attacked a train on the Phnom Pehn-Kampot line and executed dozens of people, including three westerners. In 1997, the former Khmer Rouge propaganda minister Son Sen was murdered with his wife and children on Pol Pot's direct orders--a lurid crime that led to the dictator's downfall inside his own movement. Only with Pol Pot's death in 1998 did the movement begin to peter out, and the almost supernatural fear he inspired begin to recede.

Vann Nath's electrifying, primitivist images inspired by Bollywood movie posters and drawn directly from memory, are the only testimony to what happened inside S-21, a former French school in the heart of the city where thousands were tortured and murdered under the eye of the psychopathic Duch. It's a paradox of torture (and genocide, for that matter) that it can rarely if ever actually be photographed as it happens. But it can be painted. Like Duch, Vann Nath is quite a well-known character in Phnom Pehn. He owns a large Khmer restaurant on Czechoslovakia Street with a dark dining room walled with bamboo and filled with the kind of miniature red-lit Chinese shrines that look like shrunken porn stores. He wasn't difficult to find in the end. A slightly stooped, white-haired man with a kindly, beaten-up face, he is to be found in his restaurant almost every day, self-effacingly holding court with a trickle of visitors and playing with his grandchildren.

You see at once the wounded, hunted eyes and the slight sense of bemusement--it's a face older than its years and yet somehow also younger. When you are one of only seven people who emerge alive from a killing machine that exterminated thousands, you inevitably wonder why it was you and not someone else. As Vann Nah explains in his book, he was only spared because he was a reasonably competent artist. Duch plucked him from the execution lists because he thought he might be able to produce a few decent propaganda portraits of Brother Number One, as Pol Pot was known. (The execution orders still survive, with Duch's signature at the bottom of a long list of Vann Nath's fellow prisoners and a red line under Vann Nath's name with a comment to one side suggesting that he be spared.)

We sat in the gloom of the dining room in the middle of the afternoon, under plastic vine leaves on trellises, while he ordered me a Khmer feast: mo-cou kroeung, a fiery sour soup, and spiced omelettes called pong teair. Vann Nath has his painting studio upstairs above the restaurant and, for all his odd celebrity, it's a quiet life now, by his own admission--daily painting, family and the business. Like most Khmers, he is reticent, refined, never raising his voice or making emphatic gestures. But from time to time he covers his face with a hand in a gesture of apparent nervousness. He said that he had never dreamed his life would turn out this way, that his work would become the most instantly recognizable icon of a surreal state crime. "I thought I would be painting landscapes. Indeed, I have now gone back to painting landscapes." On Jan. 7, 1978, the 33-year-old painter was arrested. As usual with the Khmer Rouge, there was no explanation, no credible charge; the whole process was somewhat mysterious.

Equally inexplicably, Vann Nah was tortured by electrocution. The questions were always the same. Was he a member of the CIA? The Vietnamese sympathizers? The KGB? He had never heard of any of them. He was then bundled into a convoy bound for Phnom Pehn, still with no idea what he had been arrested for. Instantly, he was catapulted into a Dostoyevskian world of secrecy, paranoia and terror. None of his fellow prisoners knew what they had been arrested for either. It hardly mattered. Decades later, many Khmer Rouge cadres freely admitted that most of the people they had murdered were innocent. Killing innocents was as important as killing the guilty. "Better to kill a thousand innocent people than let a single guilty one go," was one of the Khmer Rouge's cryptically absurd slogans. In the converted classrooms of S-21, prisoners were shackled together with iron bars. They were not permitted to talk, urinate, stand or even turn their bodies without asking permission from the ferocious teenage guards. If they ate cockroaches to supplement the appalling food, they were beaten savagely - sometimes to death. The guards knew, even if the prisoners didn't, that everyone there was doomed to die anyway.

Vann Nath's gripping paintings show many of these scenes: prisoners being flogged, water-boarded, their nails ripped out, their throats cut (it was rumored that blood was collected in this way and peddled to Phnom Pehn hospitals). In a 2003 documentary made by Rithy Panh, Vann Nath re-visited Tuol Sleng with some of the former guards, who were outwardly unrepentant. With demented enthusiasm, they re-enacted their cruelties - revolutionary children tormenting their elders. They stormed up and down the corridors for the cameras, screaming at the ghosts of long-dead prisoners. Vann Nath and Chum Mey, another survivor, watched them in stupefaction. "Pol Pot was always obsessed with the Cambodians disappearing as a race," Van Nath said in the restaurant. "There was this racial hysteria about the Vietnamese, about the Khmers being conquered and assimilated. But during that whole time I kept wondering if the Khmers were simply destroying themselves. I wondered, how can we do this to ourselves? Is it self-hatred? Are we trying to wipe ourselves from the face of the earth?"

We went upstairs to the open-air studio on the first floor - a terrace overlooking the tin rooftops. It was the rainy season and the skies lit up with monstrous flashes of lightning. The studio paintings were a mix: half political paintings, half idyllic, sunset-drenched landscapes filled with Ankgorian ruins, water buffalo and the timeless villages that seem to reside in the Khmer unconscious as a kitsch memory of a lost Eden. They are the kinds of images you see everywhere at Angkor Wat, sold by scores of artists by the roadside. But the Tuol Sleng images are something else. Also derived from memory, they have the gritty, driving force of a personal pathology. Among them stood one of the hallucinatory pictures of Pol Pot, clearly inspired by the iconography of Mao. Looking at it, I was reminded of a curious observation by the French writer Pierre Loti upon visiting the ruin of Banon at Angkor Wat, which is famous for its giant smiling faces of King Jayavarman VII. Loti found the temple terrifying because of those faces, which showed the smile of totalitarian power and cruelty, of calm implacability. When I told Vann Nath this he seemed to recognize the parallel. "Yes, I can see that. I made Pol Pot smile like that because that's what they wanted."

Like a miniature gulag, Tuol Sleng had its hierarchies, its survival strategies (futile in the end, of course) and its resident sadists. Over it all presided the cool, methodical, pedantic Duch, who took pride in the exactness of his bookkeeping. Every day he came into the studio, where a handful of artists were being kept alive for official purposes, and examined their progress. The executioners always came with him. I wondered how Vann Nah felt about Duch now. "Duch was always polite to me. He would come in and look at my portraits and admit that I was making a good effort. We both knew that if I didn't make that effort I would be taken out and shot with the others, but he could pretend to joke about it. He asked me to make Pol Pot look young and fresh. I ended up making him look like a teenage girl, with the pink cheeks. Duch was delighted. I was allowed to live."

Duch was himself a curious character. A former math teacher who had come under the sway of Maoism in the '60s, he was the same age as Vann Nath and had fought in the jungle army of Pol Pot for years. As it happens, he also interrogated the French scholar Francois Bizot in 1971 after Bizot was captured by the Khmer Rouge near Angkor Wat. The portrait of Duch in Bizot's book, The Gate, was unforgettable enough. Mildly sadistic and a fanatical Communist, Duch had spared Bizot because the latter could play chess and speak Khmer. This odd Frenchman was intriguing and Duch was too curious about him to have him shot. To Bizot, there was a cat and mouse quality to their relationship, and perhaps the same had been true for Vann Nath. Vann Nath's images are more than paintings, and they cannot be judged merely aesthetically. They are folk stories lit by a sudden flash of pornographic horror. His images of water-boarding, a technique used daily at Tuol Sleng, have recently found their way all over the Internet in the light of recent controversies, though few know the story behind them. For many in the West, it was their first actual image of the technique. It shows how the archaic tool of painting has once again become strangely powerful and relevant in the age of digital media.

The faded black and white photographs from 1975, "Year Zero" of the regime, often look like something from the distant past, like views of the Middle Ages. Our sense of distance from them is already extraordinary. But Vann Nath's brilliantly colored nightmares somehow remind us that most of us were alive at the time, living happy lives elsewhere. Pol Pot is not a figure from the distant past and memories are not digital. Last summer, I went every day to the trial out by the air force base. The defendants are ancient, but the machinery of U.N. justice has tried its best to be merciless toward the leaders of the genocide. (Nevermind about the thousands of subordinates who did the actual killing. They cannot be dredged up, for some mysterious reason, and they have slipped back into the population unnoticed: a thousand killers walking the streets with their shopping bags.) As the technicalities dragged on, many impatient Khmers in the audience began to hiss and mutter angrily. Many of them were survivors or relatives of the dead. One day, I was invited to accompany a group of relatives from a small country town called Takeo, who had been invited by the U.N. outreach program to visit Tuol Sleng. The idea was to teach them about what might have happened to their loved ones and to show them the place where they might have died.

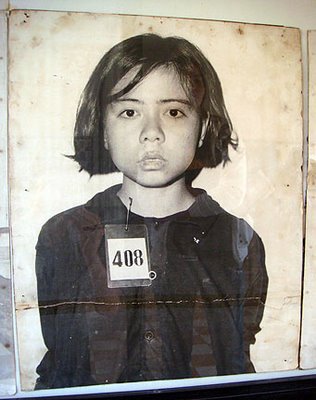

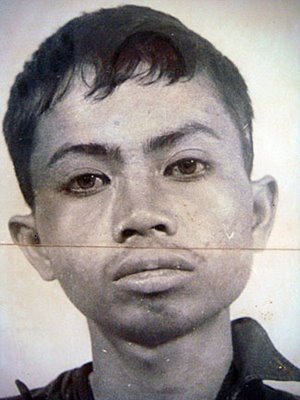

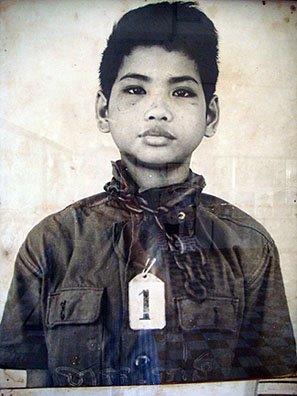

Many of these aging farmers had never been to the capital before, and Tuol Sleng to them was just a terrifying word. They arrived at the museum at 8 a.m., a large group anxious at first to have their pictures taken on the neat lawns under the shade of the frangipanis. But soon the mood changed. Tuol Sleng is filled with hundreds of mug shots taken by the captors as the prisoners were being processed prior to being "smashed." There are men, women, children--wildly beautiful young girls, old men, defiant teenagers with bloodied faces, disillusioned Party members who seem incredulous, small boys with cherubic eyes. Each one has a number slung around their neck (there is a famous Vann Nath panting of these ghastly photographic sessions). And there are pictures of the killed, too, each one with his or her throat cut, their chests cut open. There is a girl who threw herself out of a window to commit suicide. And there are the pictures by Vann Nath at every turn, exhibited here as if to corroborate the evidence. The farmers were as shocked by Vann Nath's paintings as by the portraits of the dead - perhaps more so.

Then it happened. I was standing next to a series of photos of prisoners, one of which is quite well known: It shows a young woman sitting next to her baby, her eyes turned helplessly toward the camera. Most of the portraits are marked "unknown" and this was no exception. The woman next to me was also studying this photo with excruciating intensity, and finally she let out an ear-splitting howl of grief. Tears streamed down her face. She recognized the girl with the baby. The farmers gathered round and the U.N. officials came up quickly with their notebooks; it sometimes happened t-hat a visitor recognized a dead relative, and it had happened now. The girl in the picture - the number - had a name after all, and she was the woman beside Me's sister-in-law. She had had no idea what had happened to her all those years before. The girl's name was Ouk Sareth. In the photo, she was 29. The sister-in-law's name was Nob Chim. I spent a little time with Nob Chim. She was 50 now and said she remembered "every moment" of the Khmer Rouge nightmare. Her hands shook with rage; she felt dizzy and had to sit down. She remembered she had built dams and farmed rice for Pol Pot. Ouk's husband had worked in the Ministry of Forestry and as an official had been targeted by the Khmer Rouge. He had been dragged behind a car to begin with - a little warning torture, if you like. Later, he disappeared altogether.

Ouk was sent to Tuol Sleng, it seemed, never to return. Her baby was killed as well. It is only by listening to people like Nob that you finally begin to fathom how casually the state can kill. Duch had signed Ouk's death warrant; she had shared this small prison with Vann Nath, whose Pol Pot busts stood piled up in a corner of the same room. How intimate and suffocating these interconnections were. Yet the anonymity of the regime's cruelty is strangely connected to the anonymity of its prime instigator, the man born as Saloth Sar.

It is that same anonymity that Vann Nath - consciously or otherwise - has captured in his pictures. As Nob wept, I couldn't help looking over at the impassive, smiling faces of Pol Pot that Nath had created to save his life. They explained nothing. Or did they? Vann Nath's pictures of Pol Pot are the most unnerving of all because he has captured something about the man without even wanting to. Pol Pot was always shadowy and inscrutable. He was always a smiling face in a humdrum photograph, an elusive eminence grise who ruled from behind the scenes. (During his reign, Western analysts had only been able to ascertain that Saloth Sar was Pol Pot by examining photographs of one of his state trips to China.) Inside Cambodia, many didn't know him even at the height of his power, even as they were about to die at his hands.

When Duch asked Vann Nath to put a name to a picture of Pol Pot, the confused artist said "Noun Chea." The director was highly amused, for Comrade Number One often "disappeared." He was always the puppet-master, the hidden engineer of human souls. And in Tuol Sleng one cannot help asking the question: Who was he? In a remarkable 1997 video interview with the American journalist Nate Thyer, the deposed dictator admitted, "I am not a very talkative person. … I am not a special person." He meant it. He mentioned with a shy smile that the French author Jacques Vergès had known him for 30 years "as a polite, discreet young man" but nothing more than that. Saloth was nothing if not stunningly ordinary. "Am I a violent person?" he liked to ask. How secretive the torturers always are, screened by legalisms and pseudonyms and euphemisms, their operations always carried out behind walls and closed doors - from where images can rarely travel. "If I had not painted water-boarding," Vann Nath told me one night, "people would probably not believe it had happened at all." He paused, "Let alone sawing people in half."

Labels: Khmer Rouge, Tuol Sleng, Vann Nath

Labels: Duch, Khmer Rouge Tribunal, Tuol Sleng

The screen capture is poor but so is the quality of my Year Zero dvd, but these are the 4 male survivors with the children in early 1979. Vann Nath is the tallest of the men.

The screen capture is poor but so is the quality of my Year Zero dvd, but these are the 4 male survivors with the children in early 1979. Vann Nath is the tallest of the men. Another poor quality screen capture but it shows the 4 men and the 4 young children, quoted as S-21 survivors by John Pilger in 1979

Another poor quality screen capture but it shows the 4 men and the 4 young children, quoted as S-21 survivors by John Pilger in 1979Labels: Khmer Rouge, Tuol Sleng

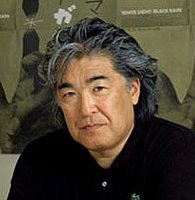

marched blindfolded into Tuol Sleng in Phnom Penh by their Khmer Rouge captors before being interrogated and then murdered, will be up for an Oscar later next month at the Academy Awards. Steven Okazaki's (pictured right) haunting story, The Conscience of Nhem En, looks behind the photos you see on the walls of S-21 at the man who was behind the camera and interviews three of the few survivors to have made it out of that hell hole. The absence of any feelings of remorse by Nhem En is chilling. ''I was only one screw of the machine. I did nothing wrong except taking photos at the superior's order,'' he claims. It will be the director's fourth Oscar nomination - he won best short in 1990 - for this short documentary, which he filmed in January of last year. It is his third film in a series of short personal documentaries, Three Journeys, which includes the Mushroom Club, a look at Hiroshima sixty years after the atomic bombing, and Hunting Tigers, a quirky look at Tokyo pop culture. Then Nhem En was a sixteen year old following orders, today he's deputy governor in Anlong Veng and has announced plans to build his own museum in the town, filled with his photographs and other KR memorablia. To find out more about the director, click here.

marched blindfolded into Tuol Sleng in Phnom Penh by their Khmer Rouge captors before being interrogated and then murdered, will be up for an Oscar later next month at the Academy Awards. Steven Okazaki's (pictured right) haunting story, The Conscience of Nhem En, looks behind the photos you see on the walls of S-21 at the man who was behind the camera and interviews three of the few survivors to have made it out of that hell hole. The absence of any feelings of remorse by Nhem En is chilling. ''I was only one screw of the machine. I did nothing wrong except taking photos at the superior's order,'' he claims. It will be the director's fourth Oscar nomination - he won best short in 1990 - for this short documentary, which he filmed in January of last year. It is his third film in a series of short personal documentaries, Three Journeys, which includes the Mushroom Club, a look at Hiroshima sixty years after the atomic bombing, and Hunting Tigers, a quirky look at Tokyo pop culture. Then Nhem En was a sixteen year old following orders, today he's deputy governor in Anlong Veng and has announced plans to build his own museum in the town, filled with his photographs and other KR memorablia. To find out more about the director, click here.Labels: S-21, The Conscience of Nhem En, Tuol Sleng

Labels: DC Cam, S-21, Tuol Sleng