Cloud cuckoo land

Labels: Anlong Veng, Khmer Rouge, Nhem En

Cambodia - Temples, Books, Films and ruminations...

Labels: Anlong Veng, Khmer Rouge, Nhem En

Bottles demarcate the edge of the funeral mound with flowers sprouting nearby

Bottles demarcate the edge of the funeral mound with flowers sprouting nearby The funeral mound of mud and ash looks like a strong wind could carry it away forever

The funeral mound of mud and ash looks like a strong wind could carry it away foreverLabels: Anlong Veng, Khmer Rouge, Pol Pot

The main building at Ta Mok's residence, which contains the wall-paintings, two upper floors and a basement

The main building at Ta Mok's residence, which contains the wall-paintings, two upper floors and a basement One of the western-style toilets favoured by the one-legged KR military chief Ta Mok - I imagine it's easier to sit than squat if you have one leg

One of the western-style toilets favoured by the one-legged KR military chief Ta Mok - I imagine it's easier to sit than squat if you have one legLabels: Anlong Veng, Khmer Rouge, Ta Mok

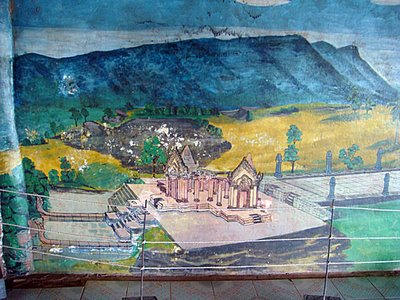

The painter of ths 1st gopura at Preah Vihear was a little limited on providing perspective in his artwork

The painter of ths 1st gopura at Preah Vihear was a little limited on providing perspective in his artwork Presumably Preah Vihear was a favourite temple of Ta Mok - it was certainly a temple that was in KR hands for long periods

Presumably Preah Vihear was a favourite temple of Ta Mok - it was certainly a temple that was in KR hands for long periods The 5th gopura at Preah Vihear shown in its mountainous location in this wall-painting on the ground floor of Ta Mok's townhouse

The 5th gopura at Preah Vihear shown in its mountainous location in this wall-painting on the ground floor of Ta Mok's townhouse Perhaps important strategy decisions were taken using this wall-painted country map on the 1st floor of Ta Mok's home

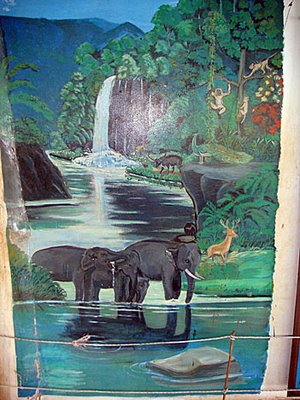

Perhaps important strategy decisions were taken using this wall-painted country map on the 1st floor of Ta Mok's home An idyllic countryside scene that never existed under the Khmer Rouge - they would've killed all these animals for their meat

An idyllic countryside scene that never existed under the Khmer Rouge - they would've killed all these animals for their meatLabels: Anlong Veng, Khmer Rouge, Ta Mok

Journalist and filmmaker Tom Fawthrop (pictured) gave an in-depth analysis of both the existing Khmer Rouge Tribunal and the circumstances surrounding his 1989 documentary at Meta House tonight, as an interested audience watched his

Journalist and filmmaker Tom Fawthrop (pictured) gave an in-depth analysis of both the existing Khmer Rouge Tribunal and the circumstances surrounding his 1989 documentary at Meta House tonight, as an interested audience watched his  Dreams and Nightmares: Cambodia Ten Years After Pol Pot film, which he directed and produced for Channel 4's Bandung series a decade after the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge regime. Fawthrop's first visit to Cambodia was in 1981 and he returned in late 1988 to film his 30-minute documentary with a film crew of just two others. The situation in Cambodia was on the change after the Vietnamese withdrawal and moves were afoot to agree some sort of peace accord between the warring factions. Hun Sen was the man in power within Cambodia but he was in no mood to surrender any ground to the Khmer Rouge or Norodom Sihanouk, who was still allied with the KR at the behest of China. The film includes interviews with Hun Sen and is clear in its message of displeasure at the international community who continued, at that time, to treat Cambodia as a pariah, favouring instead the Khmer Rouge coalition whilst conveniently ignoring the evidence of KR atrocities during the 70s. A shameful period in the history of the wider international community in my view. Screenshots from the documentary are shown here.

Dreams and Nightmares: Cambodia Ten Years After Pol Pot film, which he directed and produced for Channel 4's Bandung series a decade after the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge regime. Fawthrop's first visit to Cambodia was in 1981 and he returned in late 1988 to film his 30-minute documentary with a film crew of just two others. The situation in Cambodia was on the change after the Vietnamese withdrawal and moves were afoot to agree some sort of peace accord between the warring factions. Hun Sen was the man in power within Cambodia but he was in no mood to surrender any ground to the Khmer Rouge or Norodom Sihanouk, who was still allied with the KR at the behest of China. The film includes interviews with Hun Sen and is clear in its message of displeasure at the international community who continued, at that time, to treat Cambodia as a pariah, favouring instead the Khmer Rouge coalition whilst conveniently ignoring the evidence of KR atrocities during the 70s. A shameful period in the history of the wider international community in my view. Screenshots from the documentary are shown here.Labels: Dreams and Nightmares, Khmer Rouge, Tom Fawthrop

Labels: Anlong Veng, Khmer Rouge, Ta Mok

For the last few years, the U.N. has been sponsoring a weary, bickering, increasingly fruitless war crimes tribunal to condemn the last five senior members of the Pol Pot regime. In the summer of 2008, I watched in disbelief as Ieng Sary, the former foreign minister, was judged "unfit" to stand trial for mental health reasons. This year, it has been the turn of the sinister Duch, the commandant of Tuol Sleng. The others on trial are Khieu Samphan, the former nominal head of state; Noun Chea, Pol Pot's deputy, and Ieng Thirith. But this month in Phnom Pehn I noticed that the papers were also filled with rumors that the UN was threatening to pull out of a trial seen as being manipulated by the nervous Prime Minister Hun Sen. The slippery Hun Sen is an ex-Khmer Rouge himself, after all, and he has many skeletons in his capacious cupboards.

On the streets, meanwhile, the most ubiquitous genocide book by far is a slender volume with the modest title, A Cambodian Prison Portrait: A Year in the Khmer Rouge's S-21. Unwrap the plastic and you enter the most harrowing memoir of them all, a first-person account of the Khmer Rouge years by a naive country painter named Vann Nath: one of only seven men to survive Tuol Sleng. Sixteen thousand others were not so lucky. Some have called Vann Nath the Goya of the genocide, which was contrived by the Maoist regime of Democratic Kampuchea between 1975 and 1979. It was a period in which the strange, secretive dictator Pol Pot - whose real name was Saloth Sar - tried to create what the British historian Philip Short has called "the first modern slave state." Upon emerging victorious from a long guerrilla war against the U.S.-backed government of Lon Nol, Pol Pot's militant Khmer Rouge emptied the cities and drove millions of people into the countryside to work in collective farms. Twenty thousand died on the road in the first few days of the regime and during the next three years and 10 months, 200,000 were executed as "traitors." In total, between 1.5 million and 2 million died. When the Vietnamese army finally drove Pol Pot back into the jungles of western Cambodia, the country was strewn with the remains of the so-called killing fields.

But the Khmer Rouge did not cease to terrorize Cambodia. Supported by China, Thailand and the U.S., Pol Pot himself fought on in the wild Cardamom Mountains near the town of Pailin, on the border with Thailand. Atrocities continued. In 1994, Khmer Rouge units attacked a train on the Phnom Pehn-Kampot line and executed dozens of people, including three westerners. In 1997, the former Khmer Rouge propaganda minister Son Sen was murdered with his wife and children on Pol Pot's direct orders--a lurid crime that led to the dictator's downfall inside his own movement. Only with Pol Pot's death in 1998 did the movement begin to peter out, and the almost supernatural fear he inspired begin to recede.

Vann Nath's electrifying, primitivist images inspired by Bollywood movie posters and drawn directly from memory, are the only testimony to what happened inside S-21, a former French school in the heart of the city where thousands were tortured and murdered under the eye of the psychopathic Duch. It's a paradox of torture (and genocide, for that matter) that it can rarely if ever actually be photographed as it happens. But it can be painted. Like Duch, Vann Nath is quite a well-known character in Phnom Pehn. He owns a large Khmer restaurant on Czechoslovakia Street with a dark dining room walled with bamboo and filled with the kind of miniature red-lit Chinese shrines that look like shrunken porn stores. He wasn't difficult to find in the end. A slightly stooped, white-haired man with a kindly, beaten-up face, he is to be found in his restaurant almost every day, self-effacingly holding court with a trickle of visitors and playing with his grandchildren.

You see at once the wounded, hunted eyes and the slight sense of bemusement--it's a face older than its years and yet somehow also younger. When you are one of only seven people who emerge alive from a killing machine that exterminated thousands, you inevitably wonder why it was you and not someone else. As Vann Nah explains in his book, he was only spared because he was a reasonably competent artist. Duch plucked him from the execution lists because he thought he might be able to produce a few decent propaganda portraits of Brother Number One, as Pol Pot was known. (The execution orders still survive, with Duch's signature at the bottom of a long list of Vann Nath's fellow prisoners and a red line under Vann Nath's name with a comment to one side suggesting that he be spared.)

We sat in the gloom of the dining room in the middle of the afternoon, under plastic vine leaves on trellises, while he ordered me a Khmer feast: mo-cou kroeung, a fiery sour soup, and spiced omelettes called pong teair. Vann Nath has his painting studio upstairs above the restaurant and, for all his odd celebrity, it's a quiet life now, by his own admission--daily painting, family and the business. Like most Khmers, he is reticent, refined, never raising his voice or making emphatic gestures. But from time to time he covers his face with a hand in a gesture of apparent nervousness. He said that he had never dreamed his life would turn out this way, that his work would become the most instantly recognizable icon of a surreal state crime. "I thought I would be painting landscapes. Indeed, I have now gone back to painting landscapes." On Jan. 7, 1978, the 33-year-old painter was arrested. As usual with the Khmer Rouge, there was no explanation, no credible charge; the whole process was somewhat mysterious.

Equally inexplicably, Vann Nah was tortured by electrocution. The questions were always the same. Was he a member of the CIA? The Vietnamese sympathizers? The KGB? He had never heard of any of them. He was then bundled into a convoy bound for Phnom Pehn, still with no idea what he had been arrested for. Instantly, he was catapulted into a Dostoyevskian world of secrecy, paranoia and terror. None of his fellow prisoners knew what they had been arrested for either. It hardly mattered. Decades later, many Khmer Rouge cadres freely admitted that most of the people they had murdered were innocent. Killing innocents was as important as killing the guilty. "Better to kill a thousand innocent people than let a single guilty one go," was one of the Khmer Rouge's cryptically absurd slogans. In the converted classrooms of S-21, prisoners were shackled together with iron bars. They were not permitted to talk, urinate, stand or even turn their bodies without asking permission from the ferocious teenage guards. If they ate cockroaches to supplement the appalling food, they were beaten savagely - sometimes to death. The guards knew, even if the prisoners didn't, that everyone there was doomed to die anyway.

Vann Nath's gripping paintings show many of these scenes: prisoners being flogged, water-boarded, their nails ripped out, their throats cut (it was rumored that blood was collected in this way and peddled to Phnom Pehn hospitals). In a 2003 documentary made by Rithy Panh, Vann Nath re-visited Tuol Sleng with some of the former guards, who were outwardly unrepentant. With demented enthusiasm, they re-enacted their cruelties - revolutionary children tormenting their elders. They stormed up and down the corridors for the cameras, screaming at the ghosts of long-dead prisoners. Vann Nath and Chum Mey, another survivor, watched them in stupefaction. "Pol Pot was always obsessed with the Cambodians disappearing as a race," Van Nath said in the restaurant. "There was this racial hysteria about the Vietnamese, about the Khmers being conquered and assimilated. But during that whole time I kept wondering if the Khmers were simply destroying themselves. I wondered, how can we do this to ourselves? Is it self-hatred? Are we trying to wipe ourselves from the face of the earth?"

We went upstairs to the open-air studio on the first floor - a terrace overlooking the tin rooftops. It was the rainy season and the skies lit up with monstrous flashes of lightning. The studio paintings were a mix: half political paintings, half idyllic, sunset-drenched landscapes filled with Ankgorian ruins, water buffalo and the timeless villages that seem to reside in the Khmer unconscious as a kitsch memory of a lost Eden. They are the kinds of images you see everywhere at Angkor Wat, sold by scores of artists by the roadside. But the Tuol Sleng images are something else. Also derived from memory, they have the gritty, driving force of a personal pathology. Among them stood one of the hallucinatory pictures of Pol Pot, clearly inspired by the iconography of Mao. Looking at it, I was reminded of a curious observation by the French writer Pierre Loti upon visiting the ruin of Banon at Angkor Wat, which is famous for its giant smiling faces of King Jayavarman VII. Loti found the temple terrifying because of those faces, which showed the smile of totalitarian power and cruelty, of calm implacability. When I told Vann Nath this he seemed to recognize the parallel. "Yes, I can see that. I made Pol Pot smile like that because that's what they wanted."

Like a miniature gulag, Tuol Sleng had its hierarchies, its survival strategies (futile in the end, of course) and its resident sadists. Over it all presided the cool, methodical, pedantic Duch, who took pride in the exactness of his bookkeeping. Every day he came into the studio, where a handful of artists were being kept alive for official purposes, and examined their progress. The executioners always came with him. I wondered how Vann Nah felt about Duch now. "Duch was always polite to me. He would come in and look at my portraits and admit that I was making a good effort. We both knew that if I didn't make that effort I would be taken out and shot with the others, but he could pretend to joke about it. He asked me to make Pol Pot look young and fresh. I ended up making him look like a teenage girl, with the pink cheeks. Duch was delighted. I was allowed to live."

Duch was himself a curious character. A former math teacher who had come under the sway of Maoism in the '60s, he was the same age as Vann Nath and had fought in the jungle army of Pol Pot for years. As it happens, he also interrogated the French scholar Francois Bizot in 1971 after Bizot was captured by the Khmer Rouge near Angkor Wat. The portrait of Duch in Bizot's book, The Gate, was unforgettable enough. Mildly sadistic and a fanatical Communist, Duch had spared Bizot because the latter could play chess and speak Khmer. This odd Frenchman was intriguing and Duch was too curious about him to have him shot. To Bizot, there was a cat and mouse quality to their relationship, and perhaps the same had been true for Vann Nath. Vann Nath's images are more than paintings, and they cannot be judged merely aesthetically. They are folk stories lit by a sudden flash of pornographic horror. His images of water-boarding, a technique used daily at Tuol Sleng, have recently found their way all over the Internet in the light of recent controversies, though few know the story behind them. For many in the West, it was their first actual image of the technique. It shows how the archaic tool of painting has once again become strangely powerful and relevant in the age of digital media.

The faded black and white photographs from 1975, "Year Zero" of the regime, often look like something from the distant past, like views of the Middle Ages. Our sense of distance from them is already extraordinary. But Vann Nath's brilliantly colored nightmares somehow remind us that most of us were alive at the time, living happy lives elsewhere. Pol Pot is not a figure from the distant past and memories are not digital. Last summer, I went every day to the trial out by the air force base. The defendants are ancient, but the machinery of U.N. justice has tried its best to be merciless toward the leaders of the genocide. (Nevermind about the thousands of subordinates who did the actual killing. They cannot be dredged up, for some mysterious reason, and they have slipped back into the population unnoticed: a thousand killers walking the streets with their shopping bags.) As the technicalities dragged on, many impatient Khmers in the audience began to hiss and mutter angrily. Many of them were survivors or relatives of the dead. One day, I was invited to accompany a group of relatives from a small country town called Takeo, who had been invited by the U.N. outreach program to visit Tuol Sleng. The idea was to teach them about what might have happened to their loved ones and to show them the place where they might have died.

Many of these aging farmers had never been to the capital before, and Tuol Sleng to them was just a terrifying word. They arrived at the museum at 8 a.m., a large group anxious at first to have their pictures taken on the neat lawns under the shade of the frangipanis. But soon the mood changed. Tuol Sleng is filled with hundreds of mug shots taken by the captors as the prisoners were being processed prior to being "smashed." There are men, women, children--wildly beautiful young girls, old men, defiant teenagers with bloodied faces, disillusioned Party members who seem incredulous, small boys with cherubic eyes. Each one has a number slung around their neck (there is a famous Vann Nath panting of these ghastly photographic sessions). And there are pictures of the killed, too, each one with his or her throat cut, their chests cut open. There is a girl who threw herself out of a window to commit suicide. And there are the pictures by Vann Nath at every turn, exhibited here as if to corroborate the evidence. The farmers were as shocked by Vann Nath's paintings as by the portraits of the dead - perhaps more so.

Then it happened. I was standing next to a series of photos of prisoners, one of which is quite well known: It shows a young woman sitting next to her baby, her eyes turned helplessly toward the camera. Most of the portraits are marked "unknown" and this was no exception. The woman next to me was also studying this photo with excruciating intensity, and finally she let out an ear-splitting howl of grief. Tears streamed down her face. She recognized the girl with the baby. The farmers gathered round and the U.N. officials came up quickly with their notebooks; it sometimes happened t-hat a visitor recognized a dead relative, and it had happened now. The girl in the picture - the number - had a name after all, and she was the woman beside Me's sister-in-law. She had had no idea what had happened to her all those years before. The girl's name was Ouk Sareth. In the photo, she was 29. The sister-in-law's name was Nob Chim. I spent a little time with Nob Chim. She was 50 now and said she remembered "every moment" of the Khmer Rouge nightmare. Her hands shook with rage; she felt dizzy and had to sit down. She remembered she had built dams and farmed rice for Pol Pot. Ouk's husband had worked in the Ministry of Forestry and as an official had been targeted by the Khmer Rouge. He had been dragged behind a car to begin with - a little warning torture, if you like. Later, he disappeared altogether.

Ouk was sent to Tuol Sleng, it seemed, never to return. Her baby was killed as well. It is only by listening to people like Nob that you finally begin to fathom how casually the state can kill. Duch had signed Ouk's death warrant; she had shared this small prison with Vann Nath, whose Pol Pot busts stood piled up in a corner of the same room. How intimate and suffocating these interconnections were. Yet the anonymity of the regime's cruelty is strangely connected to the anonymity of its prime instigator, the man born as Saloth Sar.

It is that same anonymity that Vann Nath - consciously or otherwise - has captured in his pictures. As Nob wept, I couldn't help looking over at the impassive, smiling faces of Pol Pot that Nath had created to save his life. They explained nothing. Or did they? Vann Nath's pictures of Pol Pot are the most unnerving of all because he has captured something about the man without even wanting to. Pol Pot was always shadowy and inscrutable. He was always a smiling face in a humdrum photograph, an elusive eminence grise who ruled from behind the scenes. (During his reign, Western analysts had only been able to ascertain that Saloth Sar was Pol Pot by examining photographs of one of his state trips to China.) Inside Cambodia, many didn't know him even at the height of his power, even as they were about to die at his hands.

When Duch asked Vann Nath to put a name to a picture of Pol Pot, the confused artist said "Noun Chea." The director was highly amused, for Comrade Number One often "disappeared." He was always the puppet-master, the hidden engineer of human souls. And in Tuol Sleng one cannot help asking the question: Who was he? In a remarkable 1997 video interview with the American journalist Nate Thyer, the deposed dictator admitted, "I am not a very talkative person. … I am not a special person." He meant it. He mentioned with a shy smile that the French author Jacques Vergès had known him for 30 years "as a polite, discreet young man" but nothing more than that. Saloth was nothing if not stunningly ordinary. "Am I a violent person?" he liked to ask. How secretive the torturers always are, screened by legalisms and pseudonyms and euphemisms, their operations always carried out behind walls and closed doors - from where images can rarely travel. "If I had not painted water-boarding," Vann Nath told me one night, "people would probably not believe it had happened at all." He paused, "Let alone sawing people in half."

Labels: Khmer Rouge, Tuol Sleng, Vann Nath

I've some news hot off the press for you: the first-ever Phnom Penh screening of Tim Pek's feature-film directorial debut, The Red Sense, will take place on Friday 24th April at 7pm at Meta House, next to Wat Botum. After receiving a Cambofest award when it got its first Cambodian screening in Siem Reap in December, Pek's made-in-Australia film about revenge and forgiveness when a women discovers the identity of the Khmer Rouge cadre who killed her father, will be very timely considering the ongoing Khmer Rouge Tribunal that begins again today in Phnom Penh. There were fears that the film's topic was too sensitive for some to be screened here, but it will now be shown afterall. You can find out more about the film here and I'll be bringing you additional news from The Red Sense camp closer to the screening date.

I've some news hot off the press for you: the first-ever Phnom Penh screening of Tim Pek's feature-film directorial debut, The Red Sense, will take place on Friday 24th April at 7pm at Meta House, next to Wat Botum. After receiving a Cambofest award when it got its first Cambodian screening in Siem Reap in December, Pek's made-in-Australia film about revenge and forgiveness when a women discovers the identity of the Khmer Rouge cadre who killed her father, will be very timely considering the ongoing Khmer Rouge Tribunal that begins again today in Phnom Penh. There were fears that the film's topic was too sensitive for some to be screened here, but it will now be shown afterall. You can find out more about the film here and I'll be bringing you additional news from The Red Sense camp closer to the screening date.Labels: Khmer Rouge, The Red Sense, Tim Pek

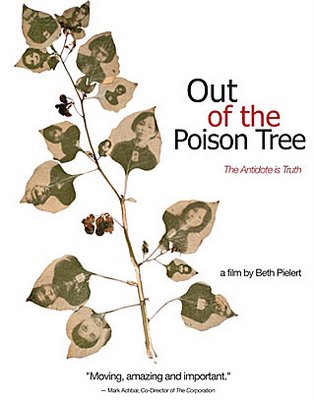

Q. Where did the idea for the film come from?

Q. Where did the idea for the film come from?Labels: Beth Pielert, Khmer Rouge, Out of the Poison Tree, Thida Buth Mam

The screen capture is poor but so is the quality of my Year Zero dvd, but these are the 4 male survivors with the children in early 1979. Vann Nath is the tallest of the men.

The screen capture is poor but so is the quality of my Year Zero dvd, but these are the 4 male survivors with the children in early 1979. Vann Nath is the tallest of the men. Another poor quality screen capture but it shows the 4 men and the 4 young children, quoted as S-21 survivors by John Pilger in 1979

Another poor quality screen capture but it shows the 4 men and the 4 young children, quoted as S-21 survivors by John Pilger in 1979Labels: Khmer Rouge, Tuol Sleng

Bonanza Three, anchored in the oily waters of Saigon harbour, seemed an ugly, rusty old tub, fit for the scrapyard, and that was the reason why she had been chosen for the Mekong River run: her owner thought her expendable. Happily for him, the American government is committed to Phnom Penh’s survival and, so far at least, it has always made it worth his while to gamble the ship and the lives of his crew for a quick return. “The risks are high, but generally so are the profits,” explained Johnny Khoo, manager of the Singapore-based shipping company that runs her. It is understood that profits fluctuate around £17,000 a trip.

The big joke aboard Bonanza Three was the loo. Apart from making privacy a farce, fist-sized shrapnel holes in the door and wall made it all too obvious that the consequences of using it at the wrong moment could prove disastrous. Happily, the Khmer Rouge gunners, notoriously bad shots, have never caught anyone with their pants down. The ship’s radio officer, I was told, was “absent”. Only later did I discover that the poor fellow had been killed two months before, blasted in his cabin by a rocket. Members of the crew had scooped up the pieces in a plastic bag and are still trying to erase this from their memories.

The convoy passed the first big danger point almost unchallenged. At Peam Chor, 15 miles beyond the frontier, the Mekong suddenly curves and narrows to a 500-yard channel – an ideal and frequent ambush spot. Conspicuous to our straining eyes were the hulks of two ammunition barges sunk 10 days before, during the last run. All that remained were pieces of rusty machinery poking from the sluggish water. With the sleepy little town of Neak Leung just a fading smudge to stern, the danger seemed over. Even Captain Pentoh relaxed, unzipping his flak jacket and pulling off his helmet, for he knew that no convoy had been hit on the home run for nearly a year. The ambush came quickly, with a rocket attack on the lead ship, the Monte Cristo, as she steamed past the Dey Do plywood factory only 12 miles from Phnom Penh.

From the wheelhouse on Bonanza Three, two ships astern, it was impossible to assess the damage, but flames and a feather of black smoke on the Wing Pengh, the ship 300 yards from our bows, denoted that she, too, had been hit. Machine-gun bullets clanged and rattled off the hull. In the wheelhouse, the little Cambodian pilot carried on with his instructions, his voice as steady as a rock, his fear betrayed only by his delicate fingers tightly wrapped round a small ivory Buddha. The words “starboard easy” had just left his lips when the rocket burst aft. The explosion felt like a heavy blow in the back. Nobody moved or said anything, except the captain, who said, “Bloody hell, we’ve been hit”, then looked around embarrassed.

Nobody bothered to leave the wheelhouse and inspect the damage until we were safely tied up at Phnom Penh’s dirty brown waterfront an hour or so later. The rocket had missed the steering column by a fraction of an inch; had it hit, Bonanza Three would have been sent circling out of control. A winch was badly damaged and there were a lot of holes, but she had survived yet another Mekong River run. Pinned to a blackboard in the press briefing centre in Phnom Penh that evening, the Cambodian high command’s communiqué tersely read: “A convoy of five cargo ships, two petrol tankers and three ammunition barges has anchored at the port of Phnom Penh after passing up the Mekong without incident.”

The Khmer Rouge captured Phnom Penh in 1975. Millions of Cambodians died in the “killing fields” massacres that followed.

Labels: Jon Swain, Khmer Rouge, Phnom Penh

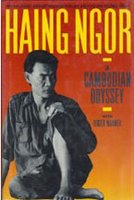

In anticipating the forthcoming publication of Bou Meng's memoir, Bou Meng: A Survivor from Khmer Rouge Prison s-21, to be published by DC Cam sometime very soon, and as I keep getting asked questions about survivor accounts and memoirs from the Khmer Rouge years, I'm listing below the memoirs of that time that I'm aware of. I'm sure I've missed some out, so let me know if you spot any omissions. I have asterisked the Top 10 books I recommend you buy. And my favourite, well it must be the incredible A Cambodian Odyssey of Haing S Ngor with Roger Warner.

In anticipating the forthcoming publication of Bou Meng's memoir, Bou Meng: A Survivor from Khmer Rouge Prison s-21, to be published by DC Cam sometime very soon, and as I keep getting asked questions about survivor accounts and memoirs from the Khmer Rouge years, I'm listing below the memoirs of that time that I'm aware of. I'm sure I've missed some out, so let me know if you spot any omissions. I have asterisked the Top 10 books I recommend you buy. And my favourite, well it must be the incredible A Cambodian Odyssey of Haing S Ngor with Roger Warner.Labels: Khmer Rouge, memoir

One author who I won't be reading anytime soon despite having written two books on her experiences under the Khmer Rouge and her eventual return to Cambodia over twenty years later, is Claire Ly (right). The reason for my tardiness is that they are both in French, with her first book also available in Italian, Polish and Khmer. But not in English, which is a shame. The author published Escape From Hell: Four years in Khmer Rouge Camps, in 2002 and followed that up with Return to Cambodia in 2007. She's also recently completed an illustrated children's book, Kosal & Moni, about how two children find out about the past. Claire Ly was a professor of philosophy when the Khmer Rouge confined her and her family to work camps after 1975. Her father and husband were murdered and she lost other close family members before she finally reached a refugee camp, from where she emigrated to France, her home today. The experiences she endured altered her Buddhist beliefs and she was baptized as a Catholic in 1983. More here in French.

One author who I won't be reading anytime soon despite having written two books on her experiences under the Khmer Rouge and her eventual return to Cambodia over twenty years later, is Claire Ly (right). The reason for my tardiness is that they are both in French, with her first book also available in Italian, Polish and Khmer. But not in English, which is a shame. The author published Escape From Hell: Four years in Khmer Rouge Camps, in 2002 and followed that up with Return to Cambodia in 2007. She's also recently completed an illustrated children's book, Kosal & Moni, about how two children find out about the past. Claire Ly was a professor of philosophy when the Khmer Rouge confined her and her family to work camps after 1975. Her father and husband were murdered and she lost other close family members before she finally reached a refugee camp, from where she emigrated to France, her home today. The experiences she endured altered her Buddhist beliefs and she was baptized as a Catholic in 1983. More here in French.Labels: Claire Ly, Khmer Rouge

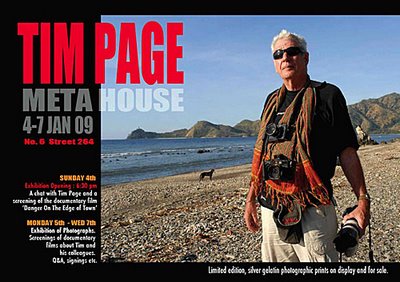

Events coming up in Phnom Penh include veteran Vietnam War photographer Tim Page's exhibition of photographs, as well as documentary screenings, Q&A's and so on at the Meta House, beginning this coming Sunday (4th) from 6pm. Also at Meta House from Saturday 3rd will be a collection of drawings titled Raining at Preah Vihear by Battambang artist Srey Bandol, who already has his drawings in print by Reyum in the book Looking At Angkor and another book aimed at children, In The Land of The Elephants. The 6pm opening on Saturday will be followed by a film/photo presentation of fellow artist Vandy Rattana.

Events coming up in Phnom Penh include veteran Vietnam War photographer Tim Page's exhibition of photographs, as well as documentary screenings, Q&A's and so on at the Meta House, beginning this coming Sunday (4th) from 6pm. Also at Meta House from Saturday 3rd will be a collection of drawings titled Raining at Preah Vihear by Battambang artist Srey Bandol, who already has his drawings in print by Reyum in the book Looking At Angkor and another book aimed at children, In The Land of The Elephants. The 6pm opening on Saturday will be followed by a film/photo presentation of fellow artist Vandy Rattana.Labels: Khmer Rouge, Svay Ken, Tim Page