Em Theay, Cambodia's finest

Em Theay, Cambodia's finestHere is another press article from the archives, this time focusing on classical Cambodian dance and my favourite icon, Em Theay. Someone has got to write a book about this lady and her unique role in the center of classical dance for the last 60 years. Her story is simply too important not to be told in every detail. She isn't getting any younger afterall. Both Unesco and the Cambodian government should stump up the funds for the book, and my choice to author it would be Denise Heywood. Maybe I should start a Facebook group to get support for my idea. Anyway, here's the story by an old Phnom Penh favourite Jon Swain.

Peace Movement

Cambodia's killing fields almost destroyed 1000 years of culture. Now the surviving dancers of the royal ballet are passing on their secrets, teaching children to perfect the elaborate steps. Jon Swain reports for The Sunday Times Magazine 7 February 1999.

Dawn comes suddenly to Cambodia. For a few treasured moments this beautiful, ravaged little country seems at peace with itself. As the sun begins to light the land, Em Theay, a 66-year-old woman with a careworn expression, leaves her tiny apartment and makes her way through the poverty-stricken streets of Phnom Penh, past the spiked pagodas and processions of monks in saffron robes, to the fine arts faculty on the other side of town. It stands at the end of a dirt track behind the French embassy and, like much of Phnom Penh, is dilapidated. The burnt-sienna and cream floor tiles are cracked and missing in places. But an enchantment awaits the eye. The hall fills with several hundred sparkling girls aged 7 to 17 - Cambodian classical ballet dancers. Their school uniforms of blue skirts and white blouses are exchanged for bright satin bodices. Long silken swathes in reds, blues and purples are bound tightly round the thighs and legs - half skirt, half trousers. The ghostly sound of bells, rising and falling unexpectedly, fills the dawn and, from all corners, hands glide onto the dance floor, unfolding with the grace of a blossoming flower. There are few visions in the world more enchantingly romantic or more apt to bring a faraway look to the seasoned traveller's eye than these dancers. Graceful and perfectly poised, their small hands alone weave amazing patterns in the air. They seem to be the sisters of those bare-breasted apsaras (the king's celestial concubines) sculpted in stone on the walls of the fabled temple of Angkor Wat. The roots of Cambodian dance lie in Angkor, the pinnacle of Khmer civilisation, which flourished more than 1000 years ago. Auguste Rodin remarked, when he saw the dancers in Paris in 1906, that it was "impossible to see human nature brought to such perfection. There are these and the Greeks."

But 20 years ago Cambodian dance was dying. Between 1975 and 1979 the country was turned into a forced labour camp under the rule of Pol Pot, the militant communist Khmer Rouge leader. As many as 1.7m people died, and its rich and vibrant culture was all but destroyed. In order to sever Cambodians' links with their past and start at Year Zero, the Khmer Rouge did away with traditional musical instruments, abolished festivals, burnt books and records and confiscated Buddhist manuscripts. The royal ballet was dissolved, and 90% of the dancers, including Em Theay's two sisters, perished through malnutrition, overwork, harsh treatment and execution in the countryside. It was an irreparable loss, but fortunately Em Theay survived the tyranny. She spent four years working in the rice fields but never forgot the dance movements she learnt from the age of seven. Brought up in the grounds of the royal palace, where her mother was a cook, she was noticed by the queen mother and personally engaged as a dancer. Because of her strong physique she was coached to play the part of the demon king in the Ramayana, the epic of Prince Rama and his wife, Sita, and was so good that she eventually became a teacher within the palace. "Amazingly, my skills saved me from death," she said. "The Khmer Rouge village leader forced me to reveal that I was a dancer and made me perform for him. He was clearly enchanted and spared me from his elimination order." When the Khmer Rouge was overthrown in January 1979, she made her way back to Phnom Penh and joined the new department of culture, for which she works to this day. Her knowledge of the ancient Cambodian dance movements stayed in her head like the secrets of a favourite recipe, and now she is passing them on.

It is a struggle. Cambodia, recovering still from years of war, neglect and suffering despite the death of Pol Pot last year and the final collapse of the Khmer Rouge, devotes less than 0.1% of its national budget to culture. The demoralised national theatre employees - 248 artists, technicians and stagehands - are lucky if they receive $10-20 a month in salary, let alone put on shows, for they lack performance space. The foyer, a triangular one-time fish pond, black with neglect, comes alive for three hours each morning, with 20 dancers practising on a torn tarpaulin lain over pebbled slabs. For the rest of the day the theatre is deserted, save for street children using it as a playground. But help has come from outside. A French theatrical producer is in negotiations to bring a touring troupe of performers to France this year, in the hope of raising Cambodia's culture profile abroad. And there has been assistance from a Japanese foundation, which has donated $30,000 for vital notation work to rescue the 60 or so dances that would otherwise vanish into oblivion. Two foreign-notation experts are busy recording the 4000 gestures on paper and videotape from the few surviving former royal palace dancers before they become too ill to pass on their knowledge, or die. The secret of making the equisite papier-mache and lacquer masks used in performances of the Ramayana was always in the hands of a few specialist families. An Sok, who learnt to make masks in the royal palace at 11 and is now 58, is one of the handful of master mask makers left. A Unesco pledge of $5000 for 30 masks for the Ramayana will go some way to helping him survive. Each mask takes a month to complete. "The faculty has received no money for the ancient art of mask-making, and it is destined to die unless I can train some young people into the business," he said at his roof-terrace workshop near the Mekong river.

Cambodian dance is a highly stylised art. Every day there is intense and painful training to make the joints so supple that the hands can bend over backwards into an agonising position nearly on the forearm. The girls sit cross-legged in rows for these tough morning exercises, moving to the thwack of the teacher's cane on the terracota. Their movements defy the laws of natural bodily suppleness: the stretching of the legs in every direction, the coaxing of the elbow joint in the opposite direction, and kness, ankles, all the joints are trained to find positions that make them look as if they will suddenly snap off. A first-year student had the audacity to grumble to Em Theay and was swiftly reminded that she was now an instrument in the service of the Cambodian king. Every day for the next 10 years these girls will repeat the same gestures until they become second nature and are of the highest refinement. Vong Metri, 44, a strikingly handsome former graduate of the fine arts university, is concentrating on teaching a group of 12-year-olds who are learning the role of Sita, the heroine of the Ramayana. "When we were in the fields we invented a new dance," she recalled. "It was called digging the ground, chopping the firewood, harvesting the rice. It was hard - terribly, terribly hard - but somehow I survived."

If the modern revival of Cambodian dance is to succeed, it will be in no small way due to the efforts of Princess Bopha Devi, King Norodom Sihanouk's daughter. She used to be the leading dancer in the royal ballet before it was smashed by war and the Khmer Rouge. With her suppleness as a dancer, she might have stepped straight out of the legends of Angkor. She is now minister of culture, a role she takes seriously, arriving often unannounced, two pekingese dogs in tow, at Em Theay's training sessions to lend a hand teaching the girls. "Dance has been in my family for generations," she said. "My mother, my grandmother - my father even played a musical instrument to accompany the royal ballet. But then it belongs to all Khmers and, as I see it, our principal aim now is the preservation of classical dance - not only dance but all of our culture. You can say that we will have to be very brave and ingenious. We are a small country with little means at our disposal, but we'll manage somehow because we have to. It is our lifeblood we are preserving here."

Labels: Em Theay, Jon Swain, Princess Bopha Devi

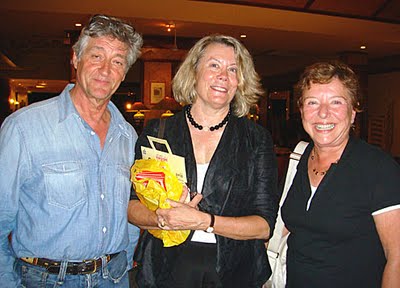

Three of the war correspondents at tonight's event, Jon Swain, Elizabeth Becker (center) and Sylvana Foa

Three of the war correspondents at tonight's event, Jon Swain, Elizabeth Becker (center) and Sylvana Foa My camera flash has managed to rob actor George Hamilton of his trademark golden tan - sorry George.

My camera flash has managed to rob actor George Hamilton of his trademark golden tan - sorry George.