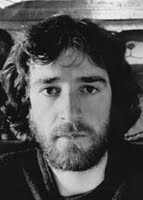

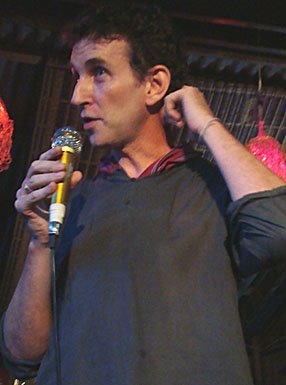

Rob Hamill

Rob Hamill

I missed this news article when it was published last week, following on from the appearance of

Rob Hamill at the Khmer Rouge tribunal as a witness. Worth re-posting here I think. You can read more about the Hamill brothers in the blog of the documentary Brother Number One

here.

Justice for a beloved brother -

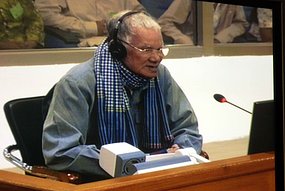

Mark Servian, Waikato Times, New Zealand 29/8/09 This month Waikato man Rob Hamill went to Cambodia to face his brother's killer in a Phnom Pehn courtroom, testifying against Khmer Rouge commander Comrade Duch. Hamilton writer Mark Servian was there as his media support, and reports on Hamill's harrowing journey.

Rob Hamill looked at the judge and said "Limeworks Loop Road, Te Pahu", and on the dusty outskirts of Phnom Pehn my vision stretched and the background seemed to retreat at the mention of that familiar hamlet in the far-away green foothills of Pirongia. Such mundane opening questions – "what is your address?" – to establish his identity. No inquiry to his character, to what he has achieved. For winning a Trans-Atlantic rowing race and breaking world records, or polling highest for the energy trust and fundraising for the hospice, all count for naught in the eyes of this Cambodian court. Here he is just another victim giving testimony, made of the same fragile human flesh that the accused there in the dock rendered and tore asunder so many times. But when asked to identify his family, Rob gives a clue to the man within – he names Kerry and John in the present tense. They ARE his brothers even now, though their deaths three decades ago is what has bought him here, face to face in this room with Comrade Duch (‘Doik’), the Khmer Rouge monster responsible, a mathematician whose victims add up to the tens of thousands.

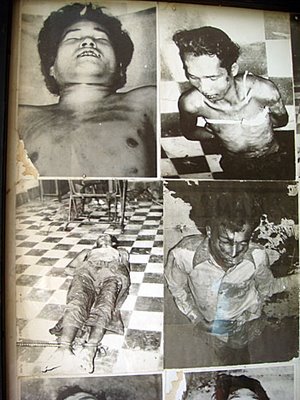

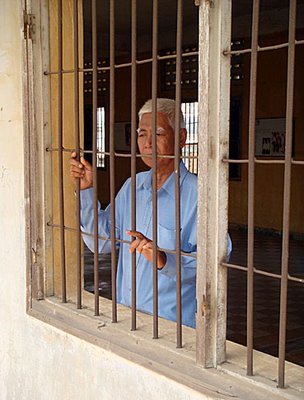

We had received word that Rob was to testify a day earlier than expected while visiting the scene of those terrible crimes. Rachel his wife, Ivan his two-year-old son and I were visiting Tuol Sleng or S21, the former high school down a Phnom Pehn back street that should be as infamous as Auschwitz. In this place, about the size of Garden Place [or Wgtn’s Civic Square or half of Chch’s The Square], Kerry Hamill landed up in 1978 with fellow lost sailor John Dewhirst. Here they were tortured and abused for months before the final release of death, along with some 15,000 to 20,000 other men, women and children.

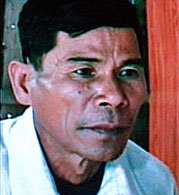

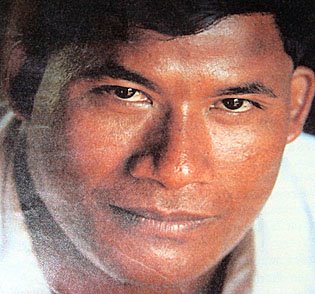

Today just inside the gate, Rachel starts crying, sobbing, for she has been living Kerry’s story for years and now she stands in the place that has loomed so large in her and Rob’s imagination. The guide asks where we’re from and we say "New Zealand", he says "I took a New Zealander whose brother was here around the other day", Rachel says, "he’s my husband". Rob visited Tuol Sleng a few days earlier and found it very hard to take. He says he arrived in Cambodia wanting to find some way in his heart to forgive Duch. But experiencing this torture factory first hand banished any chance of that. In Rob’s words, Duch "no longer belongs to the human species". For this man, who as a young student won national mathematics prizes, designed the deliberate considered processes of this torture factory. Duch alone gave the order to "smash" each and every one of his victims.

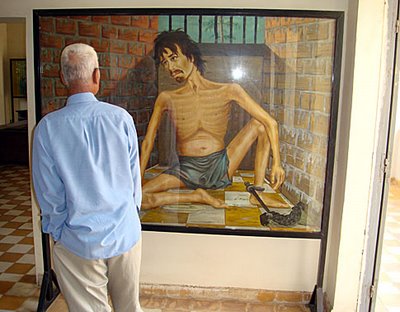

As we see and have these horrors described, Rachel’s sobbing stops. As she says later, and is as true for me, "you just feel numb after a while". We see tiny brick cells with bloodstains on the floor, balconies barb-wired to prevent escape by suicide, makeshift but efficient torture devices and tools, hundreds of photos of faces both before and after death. And actually worse of all, the paintings by Vann Nath, one of only seven survivors, that document what he witnessed. Rob later asserts that the inmates were treated like animals, but really, if animals are ever treated like this, it is called what it is - cruelty.

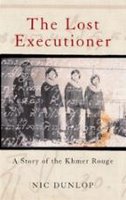

Initially ‘Angkar’, or the ‘Khmer Rouge’ as we in the West know them, only targeted the ‘new people’- the city dwellers, wearers of glasses, the intellectuals, but also factory workers and mechanics, anyone involved in the modern economy (the ‘old people’ were the rural subsistence-living ‘peasants’). But as Pol Pot’s paranoia increased, Angkar turned on their own and started torturing and killing their own ranks. The foreigners that Duch got his hands on served to prove that the enemies were at the gate, tortured into falsely confessing they were CIA or KGB agents. Kerry Hamill was killed just two or so months before the Vietnamese overthrew Pol Pot in January 1979. Before Rob’s arrival, Duch’s trial at the Extraordinary Court Chambers of Cambodia has already established that Kerry and other foreigners were burnt with tyres around their necks in order to destroy the evidence.

The debate in court has been over whether or not they were alive when this was done. A few weeks back, an ex-guard had testified that they were, but Duch maintains that he ordered that they be killed first and that no one would have disobeyed him. This is typical of how Duch has tried to run the courtroom from the dock, in a different manner but with the same intellectual arrogance that we saw from Clayton Weatherston back in New Zealand a few weeks ago. Duch converted to Christianity in the mid-90s and, unlike the other senior Khmer Rouge yet to be tried, has pleaded guilty to all charges – the court case is to decide his sentence and to cross-examine him in the French inquisitorial style. But having been arrested in 1999, he has had ten years to prepare his defence. So while he has often said sorry and asked forgiveness, his aloof behaviour in court does not match his words and he splits such horrible hairs – death by tyre or machete? – to qualify what he did. ‘I was only following orders, they would have done it to me’ is his defence. But Duch was a senior leader in the regime and, as Rob has often said, it was those in positions of power who could have stopped the madness.

Rob arrived in Cambodia the week before to prepare his testimony with Alain Werner, the Swiss lawyer representing some of the ‘civil parties’. They have redrafted it numerous times, and on this Monday Rob farewelled us to go and complete it for his scheduled appearance the next day. But mid-morning I get the call that he is likely to be on that afternoon, interrupting my, Rachel and Ivan’s numbing tour of Tuol Sleng. By the time we arrive at the crowded courthouse, thunder rumbling in the tropical sky, Rob is already in the courtroom and we are told that Ivan, being under sixteen, is not allowed in. So we take up position in the media room next door and watch proceedings via closed-circuit TV. Rob’s appearance starts with the mundane identity questions, and then he embarks on the sad tale of his brother and family. As he begins, at Rachel’s request, I call Rob’s sister who is looking after Ivan’s older brothers back in Te Pahu, handing her the phone when she answers – "Rob is on now," she says, signalling this moment none of them ever thought they would see.

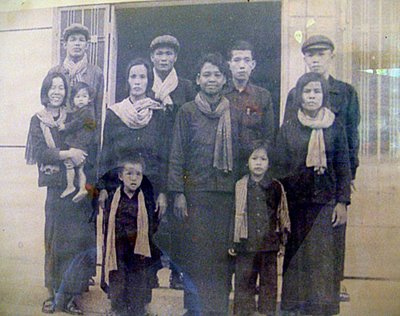

The first picture he puts up on the screen is of the Hamill brothers in a dinghy when they were kids. In this sticky warm corner of South-East Asia, the dated image of young Kiwis is jarring, prompting the Western reporters in the room to jump up and snap shots of it. As Rob then tells what happened to two of the boys on that boat, Rachel quietly cries, Ivan asleep on her lap. After half-an-hour of this gruelling testimony, the court takes a break, and suddenly Alain rushes into the room, as if he has jumped out of the screen, his lawyerly robe flapping, a bundle of energy suddenly exploding in the quiet room. He’s been sent by Rob to find Rachel, concerned that she isn’t in the courtroom with him. We explain that Ivan isn’t allowed in – "sort it out" I snap, sending Alain flying back out the door, only to return moments later to report they won’t budge. Rachel reluctantly hands me Ivan, waking the two-year-old. As she disappears the toddler objects, throwing his legs around, but eventually calming down.

When Rob resumes he starts by acknowledging his wife to the court and thanks her for her support. When he then puts up a picture of Kerry on the screen, Ivan calls out ‘Daddy!’, mistaking the uncle he’ll never know for his father. Rob continues to tell how the actions of Duch and co affected his family. As Ivan occasionally calls for his mum, it strikes me that his upset at her absence is yet one more tiny ripple of Duch’s cruelty all those years ago. Around us, the international and local media watch riveted, Rob clearly making the most intense appearance in the months-long trial. When he says to Duch "there have been times when, to use your word, I have wanted to smash you", the Cambodians in the room, some listening to translation on headphones, gasp and laugh to each other, shaking their heads in disbelief. This reaction continues as he describes how in the past he has imagined Duch suffering the tortures he has visited on so many others. It is stirring and disturbing stuff, delivered by a man who is renowned for his bravery, strength and endurance, but who today shows an emotional vulnerability that is painful to watch. Towards the end of his appearance, Rob gets the chance to ask Duch where his brother’s ashes are. Duch stands stiffly, and calmly claims that he simply doesn’t remember Kerry, though he does recall his British companion John Dewhirst .

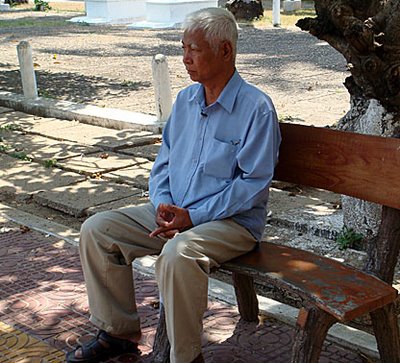

And then it is over, and Rachel reappears to reclaim Ivan and we are all shown into a side room to see Rob. There is happiness of a sort, interspersed with a sombre realisation that while the family has finally had a chance to speak their minds to Duch, many questions still remain. Ivan jumps around on the couch behind his parents, happy to have his dad back. Rob looks numb, speaking softly, smiling occasionally, a feeling of unreality pervading the room. Alain the lawyer appears and expresses his huge thanks and, his arms swinging around in an almost comically typical Gallic fashion, declares that Rob has just made the most decisive testimony of the trial.

With the crowds of the day gone, Rob steps out into the cool shadow of the building to talk to the media. He is composed, the emotion of the testimony subsided, his usual confident soap-box self to the fore again, the same as when I saw him speak at the opening of the Farmers Market at Claudelands a fortnight earlier. The media session over, Sambath Reach, the court official who has ushered us around, steps forward to speak to the small clutch of Westerners. He expresses his deep thanks to Rob "on behalf of all Cambodians" for saying things that have not previously been said in the court and for standing up to Duch in a way no one has yet dared. Like every local over forty we meet, he lost several family members to the Khmer Rouge. As he speaks, we know we are standing at a point in history.

Sambath then invites Rob over to the court’s Buddhist shrine nearby. In the warm angled tropical sun, the tall late afternoon storm clouds stacked in the distance, the Kiwi and the Khmer stand before the canopied golden warrior statue and make an offering for Kerry and all the other poor souls who fell into the hands of that dreadful beast. The pair quietly discuss the shrine’s story, the calm of the moment a blessed relief. Rob bows to the statue and thanks Sambath, squeezing his hand and meeting his eye one last time. And then he puts an arm around Rachel, picks up Ivan, and together the family walk off. Perhaps, just perhaps, the lost soul of a sailor from Whakatane, a beloved brother, can now finally rest in peace.

- Rob's search for justice for Kerry is the subject of Brother Number One, a documentary by Pan Pacific Films to be released next year.

- Mark Servian is a Hamilton writer, artist and activist.

Labels: Brother Number One, Khmer Rouge Tribunal, Rob Hamill