An Oscar for Nhem En?

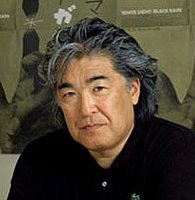

A 26-minute documentary about the man who took the photographs of the prisoners as they were  marched blindfolded into Tuol Sleng in Phnom Penh by their Khmer Rouge captors before being interrogated and then murdered, will be up for an Oscar later next month at the Academy Awards. Steven Okazaki's (pictured right) haunting story, The Conscience of Nhem En, looks behind the photos you see on the walls of S-21 at the man who was behind the camera and interviews three of the few survivors to have made it out of that hell hole. The absence of any feelings of remorse by Nhem En is chilling. ''I was only one screw of the machine. I did nothing wrong except taking photos at the superior's order,'' he claims. It will be the director's fourth Oscar nomination - he won best short in 1990 - for this short documentary, which he filmed in January of last year. It is his third film in a series of short personal documentaries, Three Journeys, which includes the Mushroom Club, a look at Hiroshima sixty years after the atomic bombing, and Hunting Tigers, a quirky look at Tokyo pop culture. Then Nhem En was a sixteen year old following orders, today he's deputy governor in Anlong Veng and has announced plans to build his own museum in the town, filled with his photographs and other KR memorablia. To find out more about the director, click here.

marched blindfolded into Tuol Sleng in Phnom Penh by their Khmer Rouge captors before being interrogated and then murdered, will be up for an Oscar later next month at the Academy Awards. Steven Okazaki's (pictured right) haunting story, The Conscience of Nhem En, looks behind the photos you see on the walls of S-21 at the man who was behind the camera and interviews three of the few survivors to have made it out of that hell hole. The absence of any feelings of remorse by Nhem En is chilling. ''I was only one screw of the machine. I did nothing wrong except taking photos at the superior's order,'' he claims. It will be the director's fourth Oscar nomination - he won best short in 1990 - for this short documentary, which he filmed in January of last year. It is his third film in a series of short personal documentaries, Three Journeys, which includes the Mushroom Club, a look at Hiroshima sixty years after the atomic bombing, and Hunting Tigers, a quirky look at Tokyo pop culture. Then Nhem En was a sixteen year old following orders, today he's deputy governor in Anlong Veng and has announced plans to build his own museum in the town, filled with his photographs and other KR memorablia. To find out more about the director, click here.

marched blindfolded into Tuol Sleng in Phnom Penh by their Khmer Rouge captors before being interrogated and then murdered, will be up for an Oscar later next month at the Academy Awards. Steven Okazaki's (pictured right) haunting story, The Conscience of Nhem En, looks behind the photos you see on the walls of S-21 at the man who was behind the camera and interviews three of the few survivors to have made it out of that hell hole. The absence of any feelings of remorse by Nhem En is chilling. ''I was only one screw of the machine. I did nothing wrong except taking photos at the superior's order,'' he claims. It will be the director's fourth Oscar nomination - he won best short in 1990 - for this short documentary, which he filmed in January of last year. It is his third film in a series of short personal documentaries, Three Journeys, which includes the Mushroom Club, a look at Hiroshima sixty years after the atomic bombing, and Hunting Tigers, a quirky look at Tokyo pop culture. Then Nhem En was a sixteen year old following orders, today he's deputy governor in Anlong Veng and has announced plans to build his own museum in the town, filled with his photographs and other KR memorablia. To find out more about the director, click here.

marched blindfolded into Tuol Sleng in Phnom Penh by their Khmer Rouge captors before being interrogated and then murdered, will be up for an Oscar later next month at the Academy Awards. Steven Okazaki's (pictured right) haunting story, The Conscience of Nhem En, looks behind the photos you see on the walls of S-21 at the man who was behind the camera and interviews three of the few survivors to have made it out of that hell hole. The absence of any feelings of remorse by Nhem En is chilling. ''I was only one screw of the machine. I did nothing wrong except taking photos at the superior's order,'' he claims. It will be the director's fourth Oscar nomination - he won best short in 1990 - for this short documentary, which he filmed in January of last year. It is his third film in a series of short personal documentaries, Three Journeys, which includes the Mushroom Club, a look at Hiroshima sixty years after the atomic bombing, and Hunting Tigers, a quirky look at Tokyo pop culture. Then Nhem En was a sixteen year old following orders, today he's deputy governor in Anlong Veng and has announced plans to build his own museum in the town, filled with his photographs and other KR memorablia. To find out more about the director, click here.Labels: S-21, The Conscience of Nhem En, Tuol Sleng

6 Comments:

Bit tough on nhem en,you say that he shows no remorse.

He was only sixteen and we know waht happened if you bucked the system.

Do any khmers show remorse over those years?

I have never heard anyone express remorse,certainly the KR leaders blamed everyone but them selves.

Any different to the ordinary german or japanese from WW2 who claim not to have known anything about atrocitities.

Well certainly Nhem En DID know about what went on. He was in the thick of it whatever he cares to say in public and remained in the inner KR circles right til the end. You are right when you say that none of the KR leaders have showed much remorse or regret for the countless deaths and Nhem En is included in that clique.

He's still in the thick of it up in Anlong Veng as deputy governor with his plans to open a KR museum to show off his photos, and no doubt, hoping to cash in on them as well. I don't have a lot of time for him as you might've guessed; his reputation precedes him.

I can't wait to see the film, its on release in the States. I hope it offers a true reflection, so we can all make our minds up one way or the other.

Cheers, Andy

A photographer with no soul - by

Hugh Hart [San Francisco Chronicle] 14 Feb 2009

On Tuesday, a U.N.-backed war crimes tribunal begins prosecuting five leaders of Cambodia's notorious Khmer Rouge regime. Better late than never, as far as Berkeley filmmaker Steven Okazaki is concerned. His Oscar-nominated short documentary, "The Conscience of Nhem En," takes viewers inside the walls of Tuol Sleng Prison. An estimated 17,000 Cambodian citizens entered the former school between 1975 and 1979. Eight lived to tell the tale. The rest were photographed, then executed.

"I've dug pretty deep into misery before, but 'The Conscience of Nhem En' is really the most difficult documentary I've ever made," Okazaki says.

He pitched HBO Documentary Films on the subject after reading about prison photographer Nhem En in 2007. When he was 16 years old, En took pictures of 6,000 prisoners shortly before their deaths.

"He came out of the woodwork because he thought he could make some money and wanted attention, I guess," Okazaki says.

Last year, Okazaki spent 2 1/2 weeks in Cambodia and questioned Nhem En on camera.

"I asked him numerous times, 'Did you ever just give these people a sympathetic look as if to say, "I'm sorry," and he said, 'Absolutely not. Why should I?' I found that disturbing. He appears to be a friendly, gentlemanly guy, but that's just on the surface. Underneath, he's a soulless, cold person."

Closely monitored by government security operatives, Okazaki managed to elicit frank accounts of incarceration from three survivors.

"Meeting these remarkable people became the great experience of making this film," Okazaki says. "They are all very emotionally scarred, but each of them has a certain spirit, and they were just lucky. One of the guys talks about being tortured for two weeks until someone came around asking, 'Does anyone know how to fix sewing machines?' He said, 'I do, I do!' That's how he got to live."

Okazaki is no stranger to bleak subject matter. He's made documentaries about teen drug addicts ("Black Tar Heroin"), Japanese American internment camps (the 1991 Oscar-winner "Days of Waiting") and nuclear devastation ("The Mushroom Club," nominated in 2006).

But "Conscience" took an unprecedented emotional toll during postproduction, he says.

"I'd blank out throughout the process of cutting the film and not know it; people would say to me, 'What happened? You just stopped talking for 10 seconds.' I found myself weeping at odd moments. I had diagnosable second-degree post-traumatic stress."

This post has been removed by the author.

Entering the Hallowed Halls of Oscar History

Four nominations puts filmmaker Steven Okazaki in an elite group of Asian American Hollywood heavyweights. By Lynda Lin, Assistant Editor. Published, Feb. 19, 2009

Steven Okazaki's fourth Academy Awards nomination got him thinking about his first time. When you've come so far,it's only natural to start looking back.

"They didn't even care," said the Sansei filmmaker with a chuckle about his first brush with Hollywood's premier

awards show in 1985 as a nominee. He was there for "Unfinished Business," his documentary on Min Yasui, Gordon Hirabayashi and Fred Korematsu, the three men who famously challenged the World War II incarceration of Japanese

Americans.

"We had to rent a Ford Taurus or something and park it in the parking structure of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion."

Since then, he's been nominated three other times including this year for the short documentary, "The Conscience of Nhem

En." A total of four Oscar nominations, which includes a win in 1991 for "Days of Waiting," puts Okazaki in an elite group of Asian Pacific American filmmakers that includes Freida Lee Mock (five-time Oscar nominee, according

to the Internet Movie Database).

In an industry famous for ignoring APAs altogether, Okazaki is a trailblazer. But he insists that the race for the Oscar doesn't get any easier with experience.

"It gets more stressful," he said by

telephone from his producer's HBO office in New York. Over the years,

Okazaki has had a steady working relationship with the cable channel. He makes the films, and they air it.

They've been able to hold screenings of "The Conscience of Nhem En" across the U.S. leading up to the awards show. Without this sort of visibility, said Okazaki, a small film like this could

disappear amidst Batman franchises and a studio film about a man aging

backwards.

News of No. 4 came during an ungodly hour in January after a rough night working on a new film project in Seattle.

"Someone from a foreign country kept calling my hotel room, so I slept through the announcements," said Okazaki. Then the call came from an HBO representative that brought a smile.

He keeps his Oscar statue at home on top of the refrigerator next to the primetime Emmy he won for "White Light/Black Rain." If Oscar is a boy, then Emmy is a girl. And he hopes to add another boy to the brood.

"My wife [writer Peggy Orenstein] made origami hats for them," said Okazaki.

Doing His Job

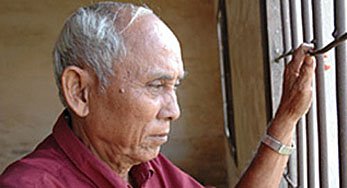

From 1975 to 1979 Cambodia's Khmer Rouge ruling party was responsible for one of the worst mass killings of the 20th century. Over 30 years later, the trials of some of the participants in the genocide have only recently begun in Cambodia.

"Like a lot of people, I've seen the photos form the Khmer Rouge genocide here and there and was always struck by them,but I didn't know much about it. I didn't know the story," said Okazaki.

Then in 2007 Nhem En, a former Khmer Rouge photographer whose job was to take pictures of the victims, made a public apology. But Okazaki got the impression that En was motivated by fame.

"His reasons were not humanitarian."

The photos — an endless number of portraits of victims in various stages of denial and terror — are of the men, women and children who died shortly after En clicked the button on his camera. Often they were tortured and killed within earshot of the photographer.

Last January, the filmmaker and his crew spent two weeks in Cambodia interviewing survivors of the notorious Tuol Sleng prison where En, then 16, took photos. Out of the about 17,000 people

taken to the prison, only eight are known to have survived. Three are

featured in the film.

The survivors are not just haunted by their past, they are possessed. It doesn't take much to make Chum Mey relive the horror he experienced when he was 42. In the film, he gets backs into the

closet-size cell at Tuol Seng to show the camera where he was taken after being tortured. He touches his feet to show how he was shackled naked. Then

he weeps.

En offered to sell Okazaki never before seen photos he kept in a manila envelop for $10,000.

"Of course as soon as I said I wasn't interested, he showed me the photos anyway."

They were mostly of En as a young Khmer Rouge soldier.

"I've never done an interview like that," said Okazaki. "I usually interview people I admire. Even with drug addicts, there was something I admired. I didn't feel any admiration [for En] and I

felt like he was holding things back.

"He did nothing. He didn't offer [the victims] a kind word or a glass of water. He just did his job. Sit down. Look forward. Click. That was it. I found it disturbing."

In his last on-camera interview, En explodes under Okazaki's forceful questioning.

"I said to him the pictures have this cruel coldness about it. Maybe it reflects the photographer."'

En's angry response is included in the film. He says he was simply doing his job. Not doing it meant he would die.

"The film is an examination of the effects of being silent when something horrible is happening to your fellow man," said Okazaki.

In it, En asks a question that would inspire the premise: would you die for your conscience?

Moving On

The film has drawn comparisons to Holocaust documentaries, but Okazaki thinks there are stronger parallels to the U.S.history of slavery and the WWII JA internment.

Tragedy can continue to affect people for generations. With the JA internment, there are still effects on people's self-esteem three or four generations later, said Okazaki. Surviving means you have to move on, but sometimes it's not so simple - even for the man

behind the camera.

"I found making the film really traumatic, almost unbearable."

He heard horrific stories that he couldn't share. HBO called the initial cuts of the film too soft and poetic for the cruelty of the subject. Okazaki argued that he didn't want to lose the audience. "What I was also saying was that I didn't want to go this deep."

So the filmmaker sought the help of a therapist for the first time because he found himself blanking out and weeping.

Let's get this straight: the man who made documentaries about the internment and the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings found this topic to difficult to digest.

"In a way, making a film on the effects of the atomic bombs was easier to process," said Okazaki. "There was a president who made a decision, someone pushed a button and all these terrible things happened. It was a political decision. The difference in

this story is that there were so many individuals who made individual

decisions without asking, 'Is this right?' What is the cost of not doing anything?"

For Okazaki, the cost is a lost soul like En.

The filmmaker has no plans to develop this into a feature-length documentary, perhaps simply because he can't bear it. En hasn't seen the film yet either, he said.

"Clearly, he is a cold and empty person," said Okazaki. "That's the price he paid."

The Academy Awards show airs Feb. 22 on ABC.'The Conscience of Nhem En' is slated to air on HBO in June. For more information on the film: www.farfilm.com.

Entering the Hallowed Halls of Oscar History

Four nominations puts filmmaker Steven Okazaki in an elite group of Asian American Hollywood heavyweights.

By Lynda Lin, Assistant Editor

Published, Feb. 19, 2009

Steven Okazaki's fourth Academy Awards

nomination got him thinking about his first time. When you've come so far,

it's only natural to start looking back.

"They didn't even care," said the Sansei

filmmaker with a chuckle about his first brush with Hollywood's premier

awards show in 1985 as a nominee. He was there for "Unfinished Business,"

his documentary on Min Yasui, Gordon Hirabayashi and Fred Korematsu, the

three men who famously challenged the World War II incarceration of Japanese

Americans.

"We had to rent a Ford Taurus or something

and park it in the parking structure of the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion."

Since then, he's been nominated three other

times including this year for the short documentary, "The Conscience of Nhem

En." A total of four Oscar nominations, which includes a win in 1991 for

"Days of Waiting," puts Okazaki in an elite group of Asian Pacific American

filmmakers that includes Freida Lee Mock (five-time Oscar nominee, according

to the Internet Movie Database).

In an industry famous for ignoring APAs

altogether, Okazaki is a trailblazer. But he insists that the race for the

Oscar doesn't get any easier with experience.

"It gets more stressful," he said by

telephone from his producer's HBO office in New York. Over the years,

Okazaki has had a steady working relationship with the cable channel. He

makes the films, and they air it.

They've been able to hold screenings of "The

Conscience of Nhem En" across the U.S. leading up to the awards show.

Without this sort of visibility, said Okazaki, a small film like this could

disappear amidst Batman franchises and a studio film about a man aging

backwards.

News of No. 4 came during an ungodly hour in

January after a rough night working on a new film project in Seattle.

"Someone from a foreign country kept calling

my hotel room, so I slept through the announcements," said Okazaki. Then the

call came from an HBO representative that brought a smile.

He keeps his Oscar statue at home on top of

the refrigerator next to the primetime Emmy he won for "White Light/Black

Rain." If Oscar is a boy, then Emmy is a girl. And he hopes to add another

boy to the brood.

"My wife [writer Peggy Orenstein] made

origami hats for them," said Okazaki.

Doing His Job

From 1975 to 1979 Cambodia's Khmer Rouge

ruling party was responsible for one of the worst mass killings of the 20th

century. Over 30 years later, the trials of some of the participants in the

genocide have only recently begun in Cambodia.

"Like a lot of people, I've seen the photos

form the Khmer Rouge genocide here and there and was always struck by them,

but I didn't know much about it. I didn't know the story," said Okazaki.

Then in 2007 Nhem En, a former Khmer Rouge

photographer whose job was to take pictures of the victims, made a public

apology. But Okazaki got the impression that En was motivated by fame.

"His reasons were not humanitarian."

The photos — an endless number of portraits

of victims in various stages of denial and terror — are of the men, women

and children who died shortly after En clicked the button on his camera.

Often they were tortured and killed within earshot of the photographer.

Last January, the filmmaker and his crew

spent two weeks in Cambodia interviewing survivors of the notorious Tuol

Sleng prison where En, then 16, took photos. Out of the about 17,000 people

taken to the prison, only eight are known to have survived. Three are

featured in the film.

The survivors are not just haunted by their

past, they are possessed. It doesn't take much to make Chum Mey relive the

horror he experienced when he was 42. In the film, he gets backs into the

closet-size cell at Tuol Seng to show the camera where he was taken after

being tortured. He touches his feet to show how he was shackled naked. Then

he weeps.

En offered to sell Okazaki never before seen

photos he kept in a manila envelop for $10,000.

"Of course as soon as I said I wasn't

interested, he showed me the photos anyway."

They were mostly of En as a young Khmer

Rouge soldier.

"I've never done an interview like that,"

said Okazaki. "I usually interview people I admire. Even with drug addicts,

there was something I admired. I didn't feel any admiration [for En] and I

felt like he was holding things back.

"He did nothing. He didn't offer [the

victims] a kind word or a glass of water. He just did his job. Sit down.

Look forward. Click. That was it. I found it disturbing."

In his last on-camera interview, En explodes

under Okazaki's forceful questioning.

"I said to him the pictures have this cruel

coldness about it. Maybe it reflects the photographer."'

En's angry response is included in the film.

He says he was simply doing his job. Not doing it meant he would die.

"The film is an examination of the effects

of being silent when something horrible is happening to your fellow man,"

said Okazaki.

In it, En asks a question that would inspire

the premise: would you die for your conscience?

Moving On

The film has drawn comparisons to Holocaust

documentaries, but Okazaki thinks there are stronger parallels to the U.S.

history of slavery and the WWII JA internment.

Tragedy can continue to affect people for

generations. With the JA internment, there are still effects on people's

self-esteem three or four generations later, said Okazaki. Surviving means

you have to move on, but sometimes it's not so simple - even for the man

behind the camera.

"I found making the film really traumatic,

almost unbearable."

He heard horrific stories that he couldn't

share. HBO called the initial cuts of the film too soft and poetic for the

cruelty of the subject. Okazaki argued that he didn't want to lose the

audience. "What I was also saying was that I didn't want to go this deep."

So the filmmaker sought the help of a

therapist for the first time because he found himself blanking out and

weeping.

Let's get this straight: the man who made

documentaries about the internment and the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings

found this topic to difficult to digest.

"In a way, making a film on the effects of

the atomic bombs was easier to process," said Okazaki. "There was a

president who made a decision, someone pushed a button and all these

terrible things happened. It was a political decision. The difference in

this story is that there were so many individuals who made individual

decisions without asking, 'Is this right?' What is the cost of not doing

anything?"

For Okazaki, the cost is a lost soul like

En.

The filmmaker has no plans to develop this

into a feature-length documentary, perhaps simply because he can't bear it.

En hasn't seen the film yet either, he said.

"Clearly, he is a cold and empty person,"

said Okazaki. "That's the price he paid."

The Academy Awards show airs Feb. 22 on ABC.

'The Conscience of Nhem En' is slated to air on HBO in June. For more

information on the film: www.farfilm.com.

Post a Comment

<< Home